Gastric varices bleeding

Gastric varices are a potentially life-threatening condition. The most common cause of gastric varices is liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Another common cause is splenic vein thrombosis, which can occur as a complication of pancreatitis or a pancreatic tumour. Patients with bleeding gastric varices usually present with hematemesis or melena, and shock if the bleeding is profound. Compared to oesophageal bleeding, gastric varices bleeding tends to be more profuse and associated with higher re-bleeding and mortality rates.

Treatment options

Primary prophylaxis is generally recommended for high-risk gastric varices and both non-selective beta-blockers and endoscopic band ligation are accepted treatment options [1]. For bleeding gastric varices, endoscopic injection of cyanoacrylate is considered the treatment of first choice [1]. Yet, failure to control the bleeding and re-bleeding within four weeks occurs in roughly 20% and 25% of patients, respectively [2]. Different radiological interventions may be applied in case of endoscopic treatment failure or as secondary prophylaxis, including transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), balloon-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) and percutaneous transhepatic obliteration (PTO).

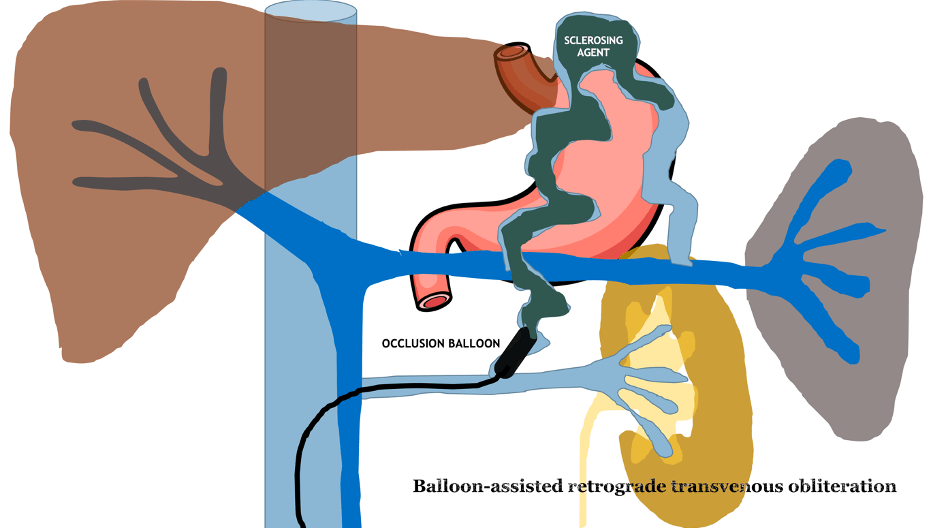

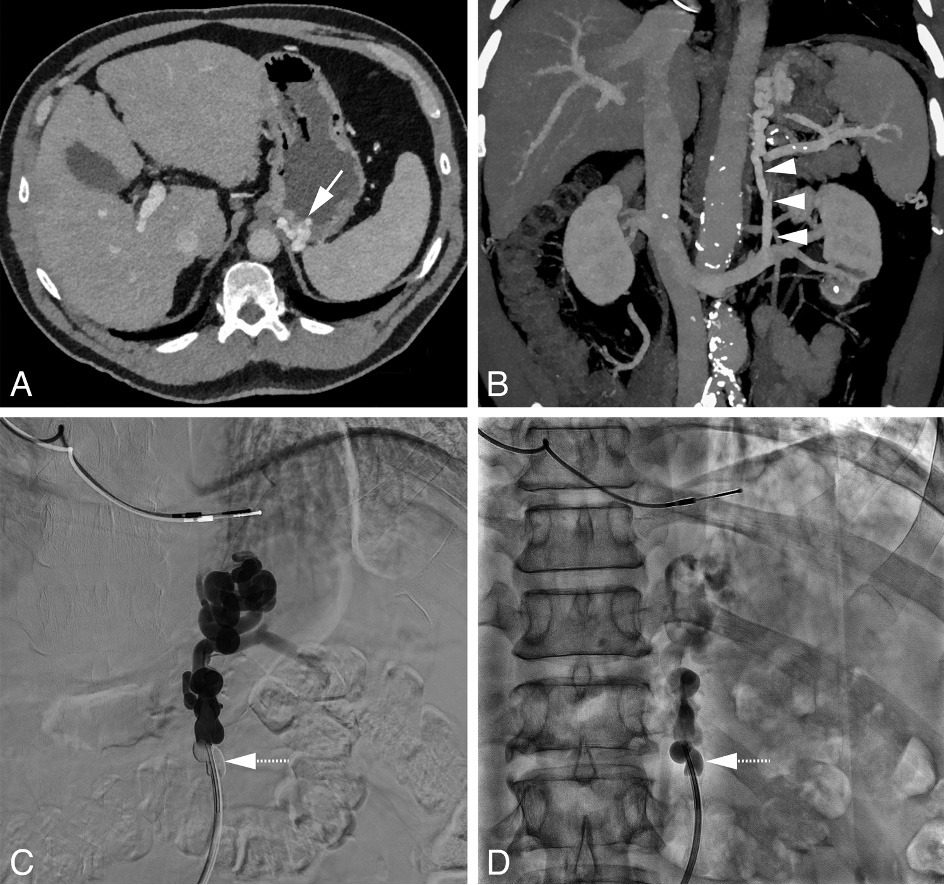

Technique of BRTO

Suitable candidates for BRTO are patients with a splenorenal shunt. Using a transfemoral approach, a catheter and guidewire are advanced via the left renal vein. The portosystemic shunt is then catheterized and occluded using an occlusion balloon (see figure 1). The purpose of the occlusion balloon is to block the flow of blood from the portal to the systemic circulation and allow retrograde filling of gastric varices with a sclerosing agent. A venogram is performed to ensure successful occlusion of the portosystemic shunt and filling of the gastric varices. It is not uncommon to see contrast agent flowing to the systemic circulation through branches originating from the portosystemic shunt, most commonly the left inferior phrenic vein. These side branches are then first embolized with coils to prevent leakage of the sclerosing agent to the systemic circulation. After successful occlusion of the shunt, a sclerosing agent, such as polidocanol or sodium tetradecyl sulfate, is injected directly into the gastric varices through the end-hole of the occlusion balloon or a micro-catheter.

Literature on BRTO

The efficacy and safety of BRTO is well established in the literature. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) including 64 patients with gastric varices bleeding, patients were randomized to either BRTO or repeated endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection as a secondary prophylaxis [3]. The probability of remaining free of all-cause re-bleeding at one and two years for cyanoacrylate injection versus BRTO was 77% versus 96.3% and 65.2% versus 92.6% (p = 0.004). Survival rates, frequency of complications, and worsening of oesophageal varices were similar in both groups. BRTO resulted in fewer hospitalizations, in-patient stays, and lower medical costs.

BRTO versus TIPS

Both TIPS and BRTO are effective therapies in case of endoscopic treatment failure or as secondary prophylaxis. Larger RCTs comparing TIPS and BRTO are currently lacking and available evidence comes from cohort studies with risk of bias. In a systematic review including eight cohort studies and a small RCT, BRTO was superior to TIPS with regards to both overall survival (RR=0.81 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.98)) and re-bleeding rate (RR=2.61 (95% CI, 1.75 to 3.90)) [4].

BRTO is widely used in the East and some regions in the United States, but in Europe TIPS is generally regarded as the primary approach for gastric varices bleeding. Advocates of TIPS generally emphasize that in BRTO, the underlying cause of the gastric varices, i.e. portal hypertension, is not addressed. However, it should be noted that the same applies to endoscopic treatment of oesophago-gastric variceal bleeding and yet the vast majority of patients are offered endoscopic therapy and are never treated with TIPS. There also is evidence indicating that BRTO may lead to long-term aggravation of oesophageal varices.

On the other hand, BRTO has several advantages over TIPS. It is not associated with encephalopathy whereas the incidence of post-TIPS hepatic encephalopathy has been reported to be as high as 35-50% in the first year after the procedure [5]. In fact, one of the indications for BRTO is encephalopathy with the presence of a splenorenal shunt, as the blood diversion caused by BRTO usually increases portal venous flow and improves hepatic function. Furthermore, BRTO is less invasive than TIPS, cheaper, and can be performed under local anaesthesia.

The wide adoption of TIPS in European countries has diverted the attention away from BRTO. Time to turn our eyes on BRTO and dive into the indications and technique of BRTO during the Case Treatment session ‘Portal Hypertension’ on the 4th of June from 10-11h!